Let’s say your organization has the best security. Your employees are trained to never fall victim to phishing. You have SSO and it’s very hard to take over your accounts. All is in perfect shape. But does everyone your company interacts with have the same high security posture? If not, then this new attack could affect you.

This truth came to light in a recent email chain impersonation attack we observed on one of our very secure customers. A hacker took over the email account of our customer’s partner, and started responding to existing threads. That part isn’t new; hackers have used the original compromised account before. In Re:Ploy, the hacker copied all of the partner’s emails to a server so they could impersonate the sender — making this attack incredibly unique.

Re:Ploy presents a new level of sophistication that imposes a new level of risk for two reasons. First, even though the partner reset their passwords to fix the account takeover, it didn’t matter. The hacker already copied all emails to their own server to impersonate the partner company and attack other organizations.

The second reason is that Re:Ploy tricks most anti-phishing and anti-impersonation algorithms. Most vendors we tested that implement such technologies think of impersonation as someone using the CEO or CFO name in an email to other employees. (Gmail and Office 365, as well as other security tools, are gradually catching up on those.) But in this case, the attack impersonates an external sender who the hackers know the recipient is familiar with.

Re:Ploy was so convincing, that even though the emails were blocked, users were asking IT to release them from quarantine.

The fake replies that we analyzed were very much in context. Therefore, we concluded they involve some company-specific effort on the hacker’s side. So, even if you see a single indicator of Re:Ploy, it is a sign that your organization is being specifically targeted by an advanced persistent threat organization.

Re:Ploy Attack Method

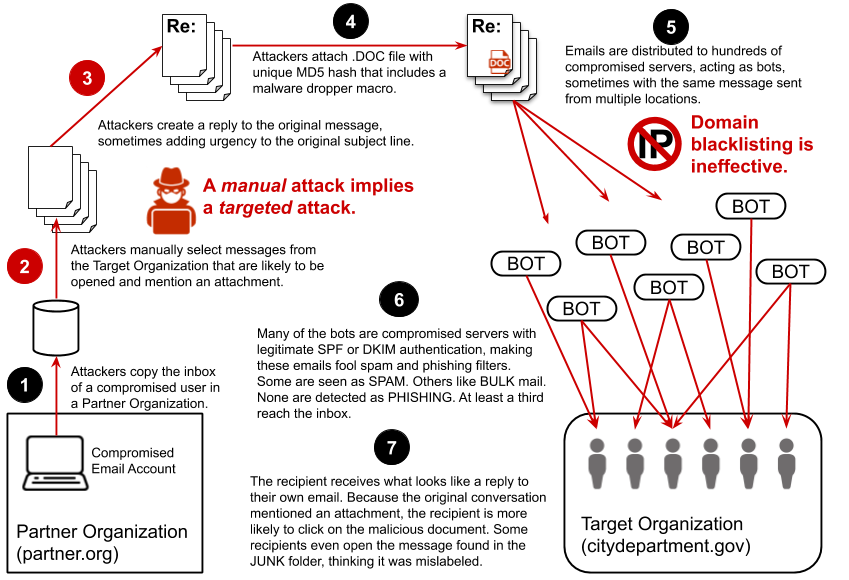

Re:Ploy started outside the target organization with the compromise of a single user within another trusted organization that has previously sent emails to the target organization.

Re:Ploy attackers searched through the inbox of the compromised user and found messages that had been sent from their ultimate target — in this case, city and county governments.

From these emails, attackers manually filtered for specific messages:

- Messages from mid-to-high-ranking individuals

- Messages from a group address that could represent multiple users (i.e. “ABCD@city.gov”), most likely including department heads

- Messages with an action item that would likely drive a user to open the email

- Messages that included a document or mentioned an attachment

Some examples of Re:Ploy subject lines*:

- “Online Survey Results on departmental activities”

- “Upcoming Emergency Training inspection form”

- “Reminder: Auditing Task Force next week”

- “New Contract - RFP 37-2019 for Fed Services and RFQ 38-2019 for State Services”

- “Agenda for today’s call”

These examples represent legitimate emails sent from the target organization and received by the compromised user.

Re:Ploy attackers manually created a reply to each email, sometimes with a small, customized note to open the attachment as a way to increase the level of trust. For example, “I’ve attached the results. If you have any questions, please contact me at tim.fletcher@partner.com.” Because the original chain might have included an attachment and requested a response, the recipient would often be expecting the message. Most of the replies included a “Re:” subject, and some were edited to increase the level of urgency:

- “Re: Departmental Services Update -- Sept 20” (added Re: and date)

- “Compliance Meeting Next Week: Updated Agenda (added “updated agenda”)

- “Re: Re: Upcoming Services Survey - last chance!” (added “Re:” to a previous reply-all and “last chance!”)

The ultimate goal of the Re:Ploy attacker is to fool the recipient to open the attached .DOC file. The manual process behinds this evidences that the attack is targeted.

The Re:Ploy Attachment

The .DOC attachment included a dropper macro that would normally have been detected but was specifically designed to bypass Office 365 malware detection. Each message included a different version of the attached document so that each displayed a different MD5 hash to avoid lookup-based detection. Re:Ploy also used another obfuscation method that we still cannot share for responsible disclosure reasons, but it seems to be linked to the Emotet attack.

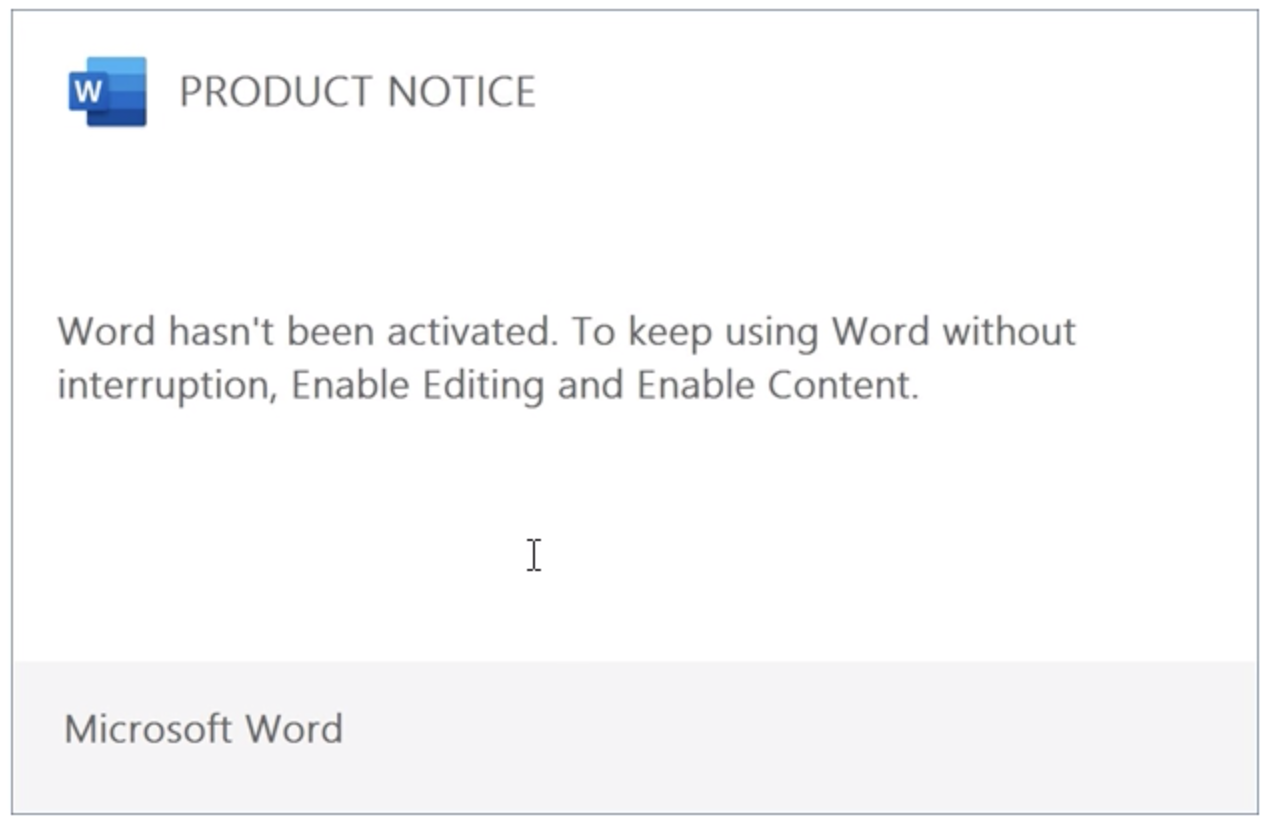

When opened, the attached file instructed the user to “enable content,” if it had not already been turned on, allowing the malicious script to run, in some cases, downloading a payload from a remote server.

The resulting behavior depended upon the downloaded malware, but in at least one case, led to the compromise of a user’s email inbox to be used in another attack.

Detection

Re:Ploy targeted government organizations that use Office 365. In a third of the cases, the malicious email would have reached the user inbox unfiltered. Because many of the distributed servers that sent the Re:Ploy attack had proper SPF authentication, the emails passed the Office 365 phishing filters.

In our analysis, more than one-third of Re:Ploy emails were considered benign (SCL=1), going straight to the inbox. In the remaining cases, the Re:Ploy emails were considered spam with an SCL score of 5 and would have gone to the junk folder (but not quarantine). In no case did the Microsoft filters flag them as malware, meaning that none were quarantined.

We have also seen hackers send the same messages to the same recipients with a few hours apart, but from separate servers. We speculate they did so to ensure that at least one copy of the message would have made it to the inbox.

Recipient Behavior

One of our customers who experienced Re:Ploy informed us that a number of employees began asking IT to release these messages from quarantine. This indicates how convincing these emails were: even after the Re:Ploy emails were blocked, users believed they were clean and wanted a copy of the attached document.

What did Avanan do?

Out of concern that hackers could weaponize the information, we don’t want to expose more details on Re:Ploy, or our solution. If you want to learn more, please schedule time with one of our Avanan experts.